Le Col de la Chipotte, 25th August 1914 – le Trou d’Enfer, the Hell Hole . Current thinking is that the soldiers on both the French and the German sides fought for the Col de la Chipotte with courage, endurance and determination. Many were inexperienced in mountain and forest combat, and the nature of the terrain undoubtedly contributed to the huge losses and injuries on both sides. One of my postcards of le Col de la Chipotte sent by a poilu from the Front instructs his wife: “Put the card in your album and save it because at la Col de la Chipotte 19000 men, French and German, fell and they are buried in the same graves.” I think his numbers may be wrong, but his sense of awe and horror is palpable.

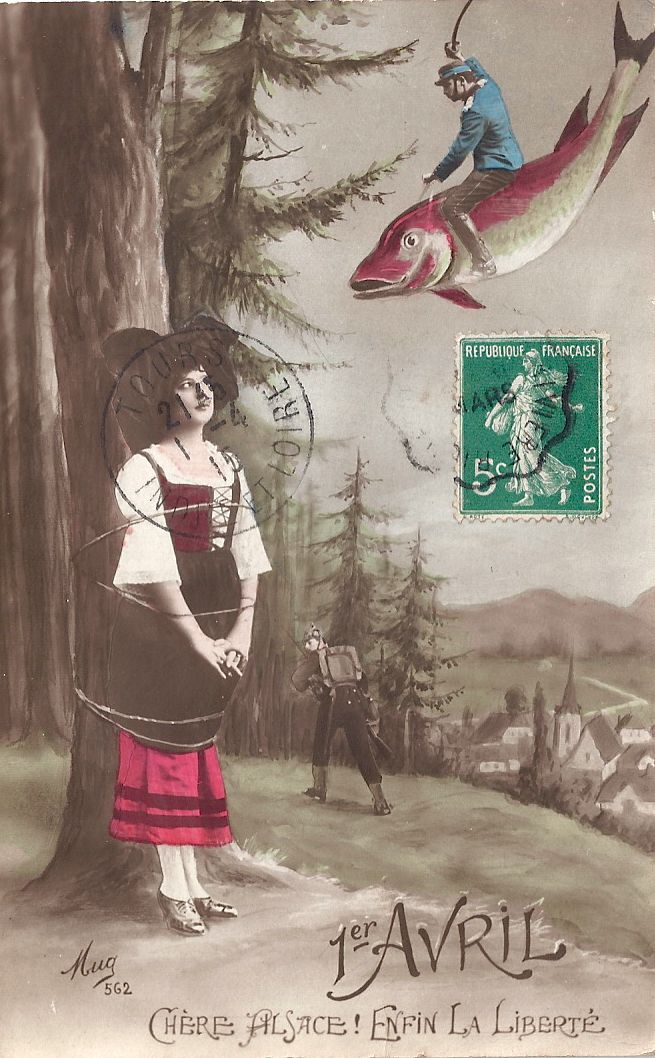

Le Col de la Chipotte (or Chipote) is in the west of the Vosges mountains on the principal route between the towns of Rambervillers and Raon-l’Étape. From Raon-l’Étape and St-Dié to its south east there are relatively easy ways through the mountains. Therefore, possession of the col was strategically vital for both the Germans and the French. Winning the Col was part of Joffre’s two-pronged strategy for reclaiming French territory lost in 1871: Alsace and Lorraine.

Before: a simple Vosges col at 453 metres.

Before: a simple Vosges col at 453 metres.

After

After

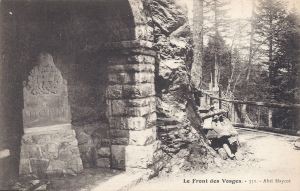

The territory is dense forest, including steep slopes and ravines. At that stage of the war, few men on either side had any experience in or training for that sort of terrain. It was almost impossible effectively to use artillery and visibility was obscured by trees. There are some small villages to the west of the col, though these were ruined by bombardment early on.

The Germans needed to be able to move their troops efficiently to other theatres of operations and by late August were in a strong position to organise their defensive strategy to progress west towards the Meurthe. On 22nd August Moltke sent the order to continue as far south as Épinal, pushing the French south and breaking their stronghold at Épinal. By the evening of the 24th August, it was considered unlikely that the French would disrupt the manoeuvres and the Germans pressed through to hold a line in the region of the villages of Étival-Moyenmoutier, Baccarat and St-Benoit in the low western foothills of the Vosges. Von Heeringen chose not to push through as far as Rambervillers and stopped at the Col de la Chipotte.

On the 25th August, the French fought back but were repelled. Some French units, separated by forests, dared not venture any further but others counter-attacked, successfully halting or even pushing back the German advance. By the evening, the Germans were ordered to suspend their forward thrust. The next day, however, they secured the forests of Sainte-Barbe. The French attacked again, somewhat overrating successes elsewhere in the region and confidently expecting their opponents to collapse.

What happened during the next day was confusing but it gives a flavour of the days to come. French unit diaries even record their soldiers hidden high in trees firing at the enemy, which may be an exaggeration. Some units failed to arrive where they were supposed to be because of failures in the transmission of orders. Others inexplicably spent the morning constructing trenches even though they had not been ordered to and the unit was not even in a status of alert. Expected reinforcements did not come. In early afternoon, the French began a retreat which quickly turned into a messy rout and by 15h00 the Germans were able to secure the col. There were already heavy casualties on both sides.

At 16h30 French troops were conscious that an attack was imminent, probably within the hour. They were heavily bombarded and hid in the woods. Panic set in and the frightened, exhausted men fled to the nearest village for shelter. Scornfully, the Germans promptly called them ‘fuyards’ [fugitives]. However, the French rallied and were able to drive the Germans back and hold the col, but at a huge cost of French lives.

On 27th, the Germans were determined to regain the Col. They needed to split the French and secure a route through the Vosges from the east to the west. The Col changed hands again and again, with a huge death toll. Despite heavy bombardments and repeated attacks over the next few days, neither side managed to secure the col.

Reports claim that this small piece of land was littered with bodies, French men lying next to Germans. One unit which started on 1st August with 3000 men and 50 officers was reduced to 1050 men and 15 officers within two days of the battle for the col. Capitaine Pasdeloup, 10e BCP, wrote on 3rd September that he was commanding the remains of two companies: 190 fusiliers instead of 500. The commandant was dead, 4 captains [plus other officers] were killed or wounded, but morale was, he said, good. On 30th August, he noted that within eight minutes of an attack on Chipotte his company lost one sergeant major, one sergeant and 41 chasseurs.

Another unit diarist recorded that between 31st August and 3rd September, his unit lost 47 killed, 252 wounded and 305 had disappeared (almost certainly dead), with 5 officers killed and 9 wounded. Out of 71 officers, he said, he had 15 left: 79% had been killed or wounded. His troops had started with 4740 men and after those 4 days there were 1905 remaining, which he said represented a loss of 60%.

In another ghastly scene, one small French unit was trapped in an isolated location surrounded by putrefying bodies for two and a half days.

In the evening of 5th September, German high command ordered its troops to cease all attacks and to prepare to move to another theatre of operations. A week later, on the 12th September, French troops reoccupied the Col de la Chipotte and fighting there ended.

Current thinking is that the soldiers on both the French and the German sides fought for the Col de la Chipotte with courage, endurance and determination. Many were inexperienced in mountain and forest combat, and the nature of the terrain undoubtedly contributed to the huge losses and injuries on both sides. One of my postcards of le Col de la Chipotte sent by a poilu from the Front instructs his wife: “Put the card in your album and save it because at la Col de la Chipotte 19000 men, French and German, fell and they are buried in the same graves.” I think his numbers may be wrong, but his sense of awe and horror is palpable.

French and Germans lie dead together.

French and Germans lie dead together.

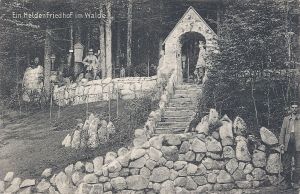

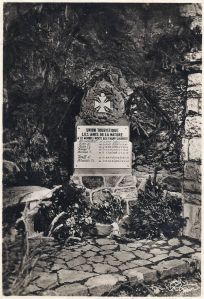

The French dead have their memorials, the Germans have none here. Cimetière Militaire de la Chipotte contains 1899 dead, plus 893 in two ossuaries. Inside the cemetery there are monuments including one to 349 unknown soldiers and a monument erected by local people (I think) to the soldiers killed on the battlefield. By the modern car parking space, there is a monument to the Chasseurs à pied and there is a roadside monument to the Colonial regiments.

September 2012

September 2012

September 2012

September 2012

Note:

Please make allowances for the fact that I am not a military historian but an enthusiast for the Vosges and their battlefields. I intend that my text should be accessible to non-specialists. I am happy to correct mistakes.

There is a full account with maps and photographs in 14-18 magazine [Le magazine de la Grande Guerre], number 59, November-January 2013. Back issues are available from the publisher. http://www.hommell-magazines.com/magpress/site/hommell/14-18-MAGAZINE/fr/kiosk/title.html

All postcards and photographs my own except for the colour photo of the cemetery, which is by Nigel Holbrook.